This past weekend, I was privileged to join University of Richmond students in the Global Health, Medical Humanities, and Human Rights Sophomore Scholars in Residence (SSIR) program for a trip to Grundy, VA to volunteer at a free clinic hosted by Remote Area Medical. Dr. Rick Mayes, the program director and my former professor at U of R, asked me to come along.

I took Dr. Mayes’s Public Health Policy class in Cusco, Peru during the summer of 2009. It was then that I started to make a connection between health disparities in underserved, third-world countries and those in my home state, West Virginia. Dr. Mayes encouraged me to challenge the U.S. health system—which I previously thought to be best in the world—and open my eyes to the idea that people at home suffer from many of the same health disparities as those in third-world countries. It was the summer of 2009 that sparked my passion for public health. So, two and a half years later, when Dr. Mayes asked me to join his group of undergrads in a trip that explored health in the Appalachian region, I jumped at the opportunity.

Here's a picture of Dr. Mayes, a classmate, and me walking to an orphanage in the outskirts of Cusco.

We left on Friday morning for our six-hour journey into the foothills of Appalachia. As soon as we arrived in Grundy, several students adamantly volunteered to stay up the entire night to help set up the clinic and hand out blankets and food to the patients who had camped out. The next morning, the students woke up promptly at 4:00 to start their shift at the clinic. (As a side note, I was late to the jump on Saturday morning. I ended up being the last one out of bed!) They worked until around 3:00 in the afternoon, without the nearest inkling of negativity. I truly can’t say enough about these students—it was so refreshing to be around a group of young people who genuinely care about others and have the courage and will to do something about it. These are the people that are changing the world for the better.

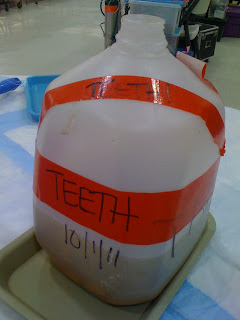

On Saturday, the RAM clinic saw around 680 patients, most of whom sought dental or vision care. I took these photos early Sunday morning of the disposal container of teeth extracted during Saturday’s clinic:

On Saturday and Sunday, RAM officials had to stop the flow of dental patients due to the enormous back-log in dentistry (which contained 34 operating dental chairs and took up the entire cafeteria in the elementary school in which the RAM clinic was held).

I worked the majority of Saturday taking basic information from vision patients as they waited in the two-hour line (do you wear eyeglasses, do you need them for reading, distance, or both, etc.). From my interactions with patients, I noticed that many of them had spent months and even years with no or inadequate vision correction. Among those with whom I spoke who did have vision correction, I only saw one person who wore contact lenses.

For me, vision correction and dental care are major facets of my life. With a -8.0 prescription in both eyes (which has continued to get worse every year since I was 8 years old) and signature Armistead teeth (which took around ten years of orthodontic work to correct), I am a clear image of someone who can lead a healthy life if given proper access to quality healthcare.

Of course, I was lucky that my parents had health, vision, and dental insurance, which was certainly a critical determining factor for receiving access to care as a child. Whether they had insurance or not, though, I know my mom and dad would have done everything they could to see that I would grow up to be healthy. Parents who are uninsured are no different. So many parents traveled hours to Grundy to stand outside in 40-degree weather and cold rain, and then to wait inside for another three hours to ensure that their children were seen by the dentist or optometrist. From my observations, parental intent for pediatric preventative care was strong in Grundy.

However, from my observations, I can’t say that the parents and other adults were focused on preventative care for themselves. If I walked down any hallway containing patients in the clinic, I couldn’t smell anything but nicotine, which had worked its way permanently into the patients’ skin, hair, and clothing. The vast majority of patients in the RAM clinic were smokers, and some had even lit up in the boys’ bathroom (of an

elementary school…that was hosting a

health clinic). Additionally, in the words of one of the RAM volunteers, the clinic “couldn’t give a pap-smear away if it tried.” Although many patients sought medical care, the line for the general medical practitioner was by far the shortest in the clinic. And last, the image above that illustrates the number of teeth extracted in just one day is a reflection of interventative, rather than preventative, focus on health.

The lack of the adults’ focus on preventative care isn’t entirely of their own fault. These are people who lead hard lives, many of them coal miners or disabled laborers. Even if they have health insurance, many people still don’t receive the benefits of dental or vision insurance. They have little access to fresh produce, and are one of the largest target populations for Big Tobacco. In Pampas Grande, we also see a heavy focus on interventative care rather than preventative care. Like the people in the Appalachian region of the United States, a multitude of factors accounts for this, including limited access to healthcare, labor-intensive lifestyles, and lack of knowledge about the benefits of healthcare. Below is a picture of one of the many patients we saw last spring at the Pampas Grande clinic having a tooth extracted:

My experiences working in these clinics have made me question what the condition of my health would be not only if I lived in a third-world village like Pampas Grande, but if I lived in a different part

of my own state. There is clearly a tremendous healthcare injustice occurring both abroad

and at home, and we have to do something about it. For the sake of human rights, we must fight against the preventable factors that lead to disease and health disparity. -

Blair Armistead

Blair Armistead is a member of RGHA and visited Pampas Grande in the springs of 2010 and 2011. She is a recent UR grad and is currently pursuing her Masters in Public Health at VCU.